By Dhanuka Bandara

“It is necessary to cultivate our garden.”

Voltaire, “Candide”

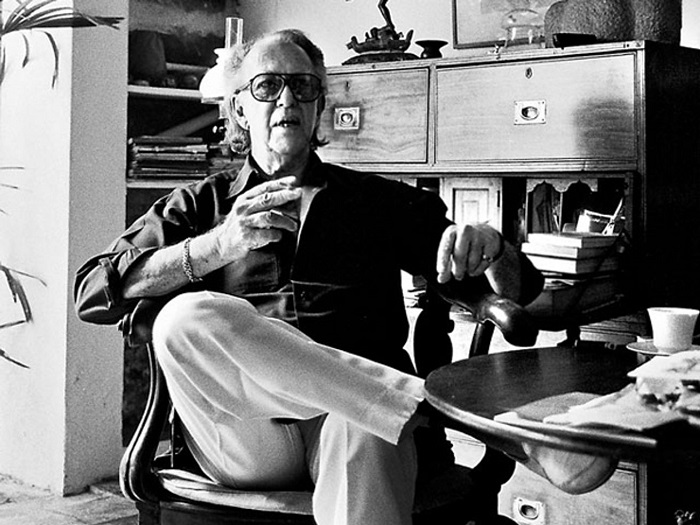

On an artificial island surrounded by the Diyavanna Oya at Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte, Sri Lanka, stands the country’s most infamous building, the Parliament Complex. The Complex was designed by arguably Sri Lanka’s most renowned architect of the 20th century, Geoffrey Bawa, built during the UNP regime of J. R. Jayewardene, and declared open in 1982.

Ever since the Parliament was moved from the old building facing Galle Face Green – the Presidential Secretariat today – to its current location, the country has gone through crisis after crisis. The 1983 anti-Tamil riots were only the beginning. This almost makes one feel superstitious. Perhaps the design of the building offended the cosmos somehow!

Ironically enough, the creator of the Complex conceived it and the surrounding city as a utopian, cosmic space. David Robson notes in Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works that

“Bawa conceived the Parliament as an island capitol surrounded by a new garden city of parks and public buildings. It would form the end point on a long promenade, beginning 8 kilometres to the west in Colombo’s Viharamahadevi Park and following the grand west-east axis formed by Ananda Coomaraswamy Mawatha, Horton Place and Castle Street before swinging southwards at Rajagiriya.”

Bawa intended the Parliament Complex as a space freely accessible to all the citizens, a garden-like space for citizens to meet their representatives, discuss matters of state, and exercise their democratic rights. Bawa’s vision, however, was only partially realized. Although the Parliament Complex stands, the surrounding garden city never materialized, and most people in the country have become disillusioned with their representatives and with the democratic process itself.

Bawa’s own home the “Lunuganga Estate” exemplifies his utopianism, which forms a strong strain in his general body of work. Bawa converted an old rubber plantation into a utopian sanctuary like space, consisting of an extensive Italianate Garden and a sprawling bungalow, with purpose built adjoining buildings. The highend tourist hotels that he designed, such as Benton Beach and Kandalama Hotel, are similarly utopian, and “paradisiacal” in their ambience.

Bawa thought of Lunuganga as a “garden in a garden,” the larger garden being Sri Lanka itself. Through his work elsewhere he sought to extend the garden of Lunuganga to encompass the whole of Sri Lanka. This grandiose vision is undoubtedly rooted in the myth that the island we now call Sri Lanka is the lost paradise.

Bawa was essentially a raging romantic, and all good romantics, consciously or unconsciously, treat Satan in John Milton’s Paradise Lost as their archetype: If you don’t get the world that you want, you must create it. It is worth noting here a fact that many critics of Bawa fail to account for: that he was a student of English literature first, a lawyer second, and an architect third.

Fortunately for Geoffrey Bawa, utopianism in architecture and landscaping is hardly without precedent in Sri Lanka. The Ranmasu Uyana in Anuradhapura, the Sigiriya fortress, and Kandy city come to mind immediately. Thus, there was already a utopian, romantic tradition that Bawa could readily draw upon in Sri Lanka.

However, he was hardly the first architect or landscape artist to draw upon, or be influenced by, this tradition. An earlier, and at this point an obscure figure who, like Bawa, wanted to create his own private Eden, was Maurice Talvande. French born Talvande, who styled himself as Count de Mauny Talvande, created the “Taprobane Island” off the coast of Weligama. His lotus shaped villa in Taprobane Island is unmistakably influenced by the rich architectural legacy of Sri Lanka.

During Count de Mauny’s time, the villa was surrounded by extensive gardens. His vision was to create a private paradise on earth. He writes in his memoirs, The Gardens of Taprobane

“Was I not looking for the one spot which, by its sublime beauty, would fulfil my dreams and hold me for life? I sought, and in the course of my endless seeking Destiny one morning made me discover the ‘Isle of Dreams’.”

That Count de Mauny named his “Isle of Dreams” as Taprobane, the Greek name for the island Sri Lanka, is quite revealing.

He further writes

“I like the name; it suits the rock, for its pear-shaped outline is like that of a miniature of Ceylon.”

Thus, despite being a foreigner, Count de Mauny, like Bawa, seems to have embraced the mythos of Sri Lanka as the lost paradise and his own island was to serve as the metaphor for the whole.

It is also pertinent to note that Taprobane Island was quite possibly a determining influence on Minette de Silva, an early pioneer of architectural modernism in Sri Lanka who visited the island when she was young.

The University of Peradeniya is another important example for utopianism in architecture and landscaping in Sri Lanka. Famous for its scenic beauty, the University is an architectural odd mix that combines a stripped international style with the architectural features of Kandy, Anuradhapura, and Polonnaruwa. The “pavilions” at Peradeniya are topped with Kandyan “pitched roofs”, while the Senate Building resting upon stone pillars remind one of the Lovamahapaya of Anuradhapura.

Although Peradeniya has been much romanticized in song and literature, it does not seem to have many admirers in the architecture community, for some strange reason. Minette de Silva was asked to serve as assistant to the Chief Architect, Shirley de Alwis, an offer she refused on grounds of creative difference: a decision that, as her memoirs show, she later regretted.

David Robson casually dismisses the architectural significance of Peradeniya, along with Independence Square – another project in which Alwis was involved – in Colombo, as an “ill-conceived attempt to create a new national architectural style using pastiche historical forms.” I find this charge bewildering given that Bawa’s work, which Robson greatly admires, is also a “pastiche of historical forms.”

The University of Peradeniya was designed and built without gates, a fact that is unfortunately not true anymore. In some ways like Bawa’s conception of the Parliamentary Complex, the University of Ceylon was conceived as a place seemingly open to all. It is a “sanctuary” like place that anybody is free to come in. In the last few years this has changed, and some entrances are now gated: a true eyesore. Those who have made the decision to do this seem to have made a crucial error of judgement.

The “openness” at Peradeniya also signifies its exact opposite. Although it is open to all, as a university its duty is to maintain standards and as such to “gatekeep”: include those who it deems deserving and exclude others. Therefore, putting up physical barriers, ironically enough, reveals the failure to gatekeep in this academic border, and even more so philosophical sense.

There is much that contemporary city planning or development in Sri Lanka can learn from this romantic, utopian vision. Today, Colombo is not the garden city that it once was and aesthetically it is hardly any different from any other developed city anywhere else in Asia. Colombo seems to have fully embraced the neoliberal urban aesthetic, and its skyline is dotted with gaudy, garish skyscrapers, which are often exclusively the preserve of the elites.

Many in Kandy would describe their once glorious city as a veritable dump. It is a far cry from the “cosmic city” that, according to Gananath Obeyesekere, Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe intended it to be. Unplanned, haphazard urban development in atrocious taste in architecture and landscaping has turned most Sri Lankan cities and towns into eyesores.

Yet, as I have argued in this article there is an alternative, and in some ways “homegrown” tradition in architecture and landscaping that we can readily draw upon.

Drawing on that utopian or romantic tradition, allow me to make the following suggestion: Sri Lankan cities should be developed as garden cities, with buildings dotting the greenery. Such cities will not only be aesthetically pleasing but also ecofriendly, and they can also attract tourists who are unlikely to be impressed by yet another tower or a skyscraper.

A key figure who can teach us valuable lessons in city planning of this sort is Ulrik Plesner, who was once Geoffrey Bawa’s associate. Plesner headed the Mahaweli Architecture Unit, and in that capacity he led the design and construction of Mahaweli towns, most of which remained unfinished.

Ulrik Plesner was heavily inspired by local traditions of city planning. In his memoir In Situ, he condenses his philosophy of city planning for Sri Lanka in several brief points:

“Shade is beautiful, and a nice place to be in. Shops must have wide roofs shading the pavement. Shade trees to be planted on pavements, public squares and parking places.”

“Vehicles and bullock carts must have access to every place as well as convenient parking, but they must not dominate or poison the town. ‘Main Streets’ are therefore either pedestrian streets or preferably, streets with limited and difficult vehicle access.”

Instead of the neoliberal concrete jungles they are gradually becoming, our cities should attempt to recover and emulate the romantic tradition in architecture and landscaping that seeks to strike a balance between culture and nature. Instead of blindly recreating the western template, we should attempt to resurrect the utopian vision of city planning that Bawa and others championed. Thus, we can all become the inhabitants of the garden, albeit a cultivated garden.

Dhanuka Bandara is a freelance writer based in Kandy, Sri Lanka. He holds a PhD in English Literature from Miami University, USA. He has taught English at Miami University and the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. He can be reached at bandard@miamioh.edu.

Factum is an Asia Pacific-focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation and Strategic Communications accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.