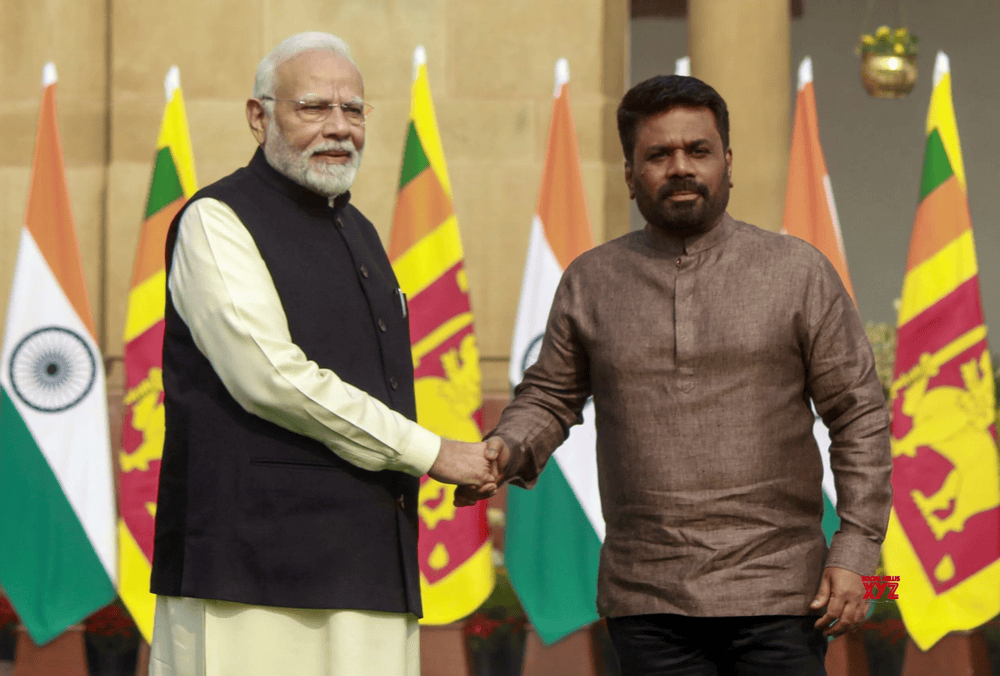

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is set to land in Sri Lanka on Friday, April 4. Over the next two days he is expected to engage with the Sri Lankan government over several agreements and pacts, encompassing trade, health, education, energy, and of course defense.

News reports point to six agreements in total. These range from power grid connectivity to health and education cooperation. The most significant among them is a defense MOU, said to be the first that Sri Lanka and India have signed: according to Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath, the basic framework for the agreement was drafted last December. Also up for discussion is the now all but completely cancelled Adani wind power project.

Power and energy, in fact, will take as much precedence as defense during his tour. While visiting the Sri Maha Bodhiya in Anuradhapura, for instance, he will launch two projects involving the railway. The location is symbolic. Around two years ago, proposals were made to link India’s and Sri Lanka’s grid through a 400 kV link from Madurai to Anuradhapura. While such initiatives have long histories and, as I noted at the time in Factum, have been so controversial as to make it difficult to reach a consensus on their viability, New Delhi has always been hopeful of greater grid connectivity with its neighbor to the south. And this time, it may not return with empty hands.

The elephant in the room is obviously Adani. The company has faced too much of a blowback to ever completely regain its reputation. The current government in Sri Lanka came to power on the strength of its opposition and resistance to the wind energy project: the NPP alliance has made it clear now that it will not proceed unless the company agrees to the government’s proposed price, which is about half Adani’s rate. While Adani does has not given up on talks with the government, it may take Modi to convince Colombo to continue negotiations, tough as they may be.

All this is doubtless big on Modi’s mind as he prepares himself for the visit, which unfolds two days after Trump’s reciprocal tariffs come into effect. India has not been spared from Trump’s moves, even if Modi’s visit to the White House implied otherwise. Despite the friendly overtures, Delhi’s ties with the US are set to take a turn. It is essentially Janus-faced: India is too important a partner for the US in the Indo-Pacific, but Trump can’t stop insinuating that the world, including India, owes Washington something or the other. Elon Musk’s dealings with the country are a case in point: while Starlink reached a deal two weeks ago with Jio and Bharti Airtel, the two biggest telecom companies in India, Musk has since sued the government for allegedly “censoring” X.

Sri Lanka is the first major destination in the neighborhood for Modi after Mauritius, which he visited last month (March 12) during its national day celebrations. There also, New Delhi signed a defense pact, in effect upgrading bilateral ties to an “enhanced strategic partnership.” It is likely that a similar pact will be finalized, and the same rhetoric amplified, during Modi’s visit here.

All things considered, this may mark a second turning point in India Sri Lanka relations, the first being the 2023 Joint Vision statement: a document praised by some commentators as a step forward and others as posing a risk to the island’s security if not sovereignty. Enough and more analyses have noted the irony of a historically anti-Indian party, and formation, now advocating for greater ties between the two countries. However, this fails to acknowledge that, even while in Opposition, as early back as 2022, the NPP acknowledged that the country “cannot have a political or economic agenda… which either ignores or forgets India.” A year and a half later, of course, the NPP was invited by Delhi on an official visit – which significantly boosted its credibility.

For India, the primary challenge now lies in responding to the shifting geopolitics of the region while accommodating domestic perceptions of Indian influence in Sri Lanka. It is noteworthy that Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka coincides with a shift in US power plays in the Indo-Pacific. While Washington has doubled down on its geostrategic objectives in the region, it has reduced its soft power footprint in countries like Sri Lanka. Both India and China are aware of this. Indeed, in the aftermath of the recent earthquake in Myanmar, both Delhi and Beijing were quick to arrive on the scene: in terms of humanitarian aid, both have been able to surpass the United States.

As far as New Delhi is concerned, hence, there is bound to be a race in the diplomacy game. Yet India has suffered a backlash with many of its neighbors in the subcontinent, the most recent example being Bangladesh. Sri Lanka offers a contrast in this regard, partly because the country is engaging in economic recovery efforts and partly because Sri Lanka’s relations with India have always been premised on an acknowledgement of the importance of India for Sri Lanka’s growth ambitions. This is why Sri Lanka has not fundamentally wavered in its diplomatic ties to Delhi.

Yet far more so than with China, Sri Lanka’s official engagements with India have been at great variance with grassroots perceptions of India. The previous government, which waxed eloquent on the benefits of physical integration with India, suffered a blowback at the presidential polls partly because of the opposition’s mobilization of anti-Indian sentiment. If history is a good guide, Delhi has managed to bounce back with whatever party in power – as it seems to have with the current Sri Lankan government. The sole exception in this regard, the J. R. Jayewardene regime (1978 – 1988), is today invoked as a classic case study for how not to conduct relations with India.

This is not to say that anti-Indian sentiment, on the ground or in local politics, has died down, or for that matter simmered. It has now passed to other parties and movements. The NPP has been tame in its response to Indian interventions. One can argue that it has no choice, as the governing party. Yet all indications are that opposition parties on the left and right will seize the opportunity to deal the anti-India card. The People’s Struggle Alliance (PSA), for instance, headed by the JVP’s (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, the leading party in the NPP alliance) ideological archrival the FSP (Frontline Socialist Party) has warned against integration with India , justifiably framing it as a national security and sovereignty issue. Modi’s entourage, which includes not just External Affairs Minister Jaishankar but also National Security Advisor Ajith Doval and Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri, has only helped in amplifying these concerns and remarks in Sri Lanka.

Of course, ultimately, the problem has to do with both sides. But how so? Just as Sri Lanka has yet to acknowledge the inevitability of India’s geopolitical ambitions in the region, India has not done a proper assessment of how those ambitions are perceived in Sri Lanka. There is, even at official levels, an almost dismissive attitude towards concerns over Indian interventions, for instance worries about giving access to national biometrical identification data here – and a refusal to engage with those concerns, for instance via a perception mapping exercise. Yet without such engagement, it is hard to predict the road ahead for ties between the two countries.

It is noteworthy, though perhaps not surprising, that while Sri Lanka has in its press releases been austere and restrained about the agreements that will be signed during the visit, the Indians have given greater emphasis to the historical and civilizational bonds between the two countries. This is not to say that there is a discrepancy in terms of priorities; just that for India, Sri Lanka remains more important than ever as a partner in the pursuit of its geopolitical ambitions. Also noteworthy is the fact that the Indian External Affairs Ministry has in its press release coupled Narendra Modi’s visit to Thailand (where he is scheduled to meet the Prime Minister on April 3) with his subsequent tour of Sri Lanka, incorporating both countries in India’s “commitment to its ‘Neighborhood First’ policy, ‘Act East’ policy, MAHASAGAR (Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth Across Regions) vision, and vision of the Indo-Pacific.” For Delhi, South Asia has become as important as the wider Indian Ocean – and Sri Lanka has become a key pivot in both spheres.

It is against this backdrop that Modi’s latest visit to Sri Lanka – his first since 2019 – must be seen and analyzed. Since the Indian government’s announcement of the visit, there has been a slew of op-eds and commentaries in the Sri Lankan media on the benefits as well as the dangers of integration with India, from the overtly optimistic to the unremittingly critical. While some paint India as Sri Lanka’s civilization partner or twin, others point to what they see as its neocolonial ambitions in the country and region. Yet both sides miss the point about Prime Minister Modi’s visit: that it is as concerned with maintaining continuity, the way things are between two neighbors, as it is with setting the stage for the next stage in bilateral ties, via energy or defense cooperation.

Uditha Devapriya is the Chief Analyst – International Relations at Factum and can be reached at uditha@factum.lk.

Factum is an Asia-Pacific focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation, Strategic Communications, and Climate Outreach accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.