By Kalani Kumarasinghe

It has been six years since suicide bombers ripped through churches and hotels across Sri Lanka, leaving behind a trail of ruined lives, scorched sanctuaries, and unanswered questions. On that April morning in 2019, the country stood still — not in reverence, but in horror. Today, the pain persists. So does the silence.

For many survivors, justice has remained elusive. While governments marked timelines and courts counted hearings, they have counted years — four presidents and three governments later — still waiting for closure.

A failure foretold

By now, the story is familiar. Islamist extremists affiliated with the National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ), guided by Zahran Hashim, orchestrated coordinated attacks on Easter Sunday. St. Anthony’s Shrine in Colombo, St. Sebastian’s Church in Negombo, and Zion Church in Batticaloa bore the brunt of the assault. Three five-star hotels — Shangri-La, Cinnamon Grand, and Kingsbury — turned from warm celebrations to sites of carnage.

Even before the smoke had cleared, the questions began — how did this happen, and who allowed it? More troubling still, fragments of answers emerged almost immediately, only deepening the sense of outrage and absurdity.

Investigations revealed that Indian intelligence agencies had warned Sri Lankan authorities of an impending attack — not once, but multiple times. The warnings were detailed, naming suspects and probable targets.

The government of the day, then fractured between President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, proved catastrophically ineffective. The security apparatus failed, not for lack of information, but for lack of will. The apology appeared insincere, after a relay of denying responsibility between the two leaders.

Justice in fragments

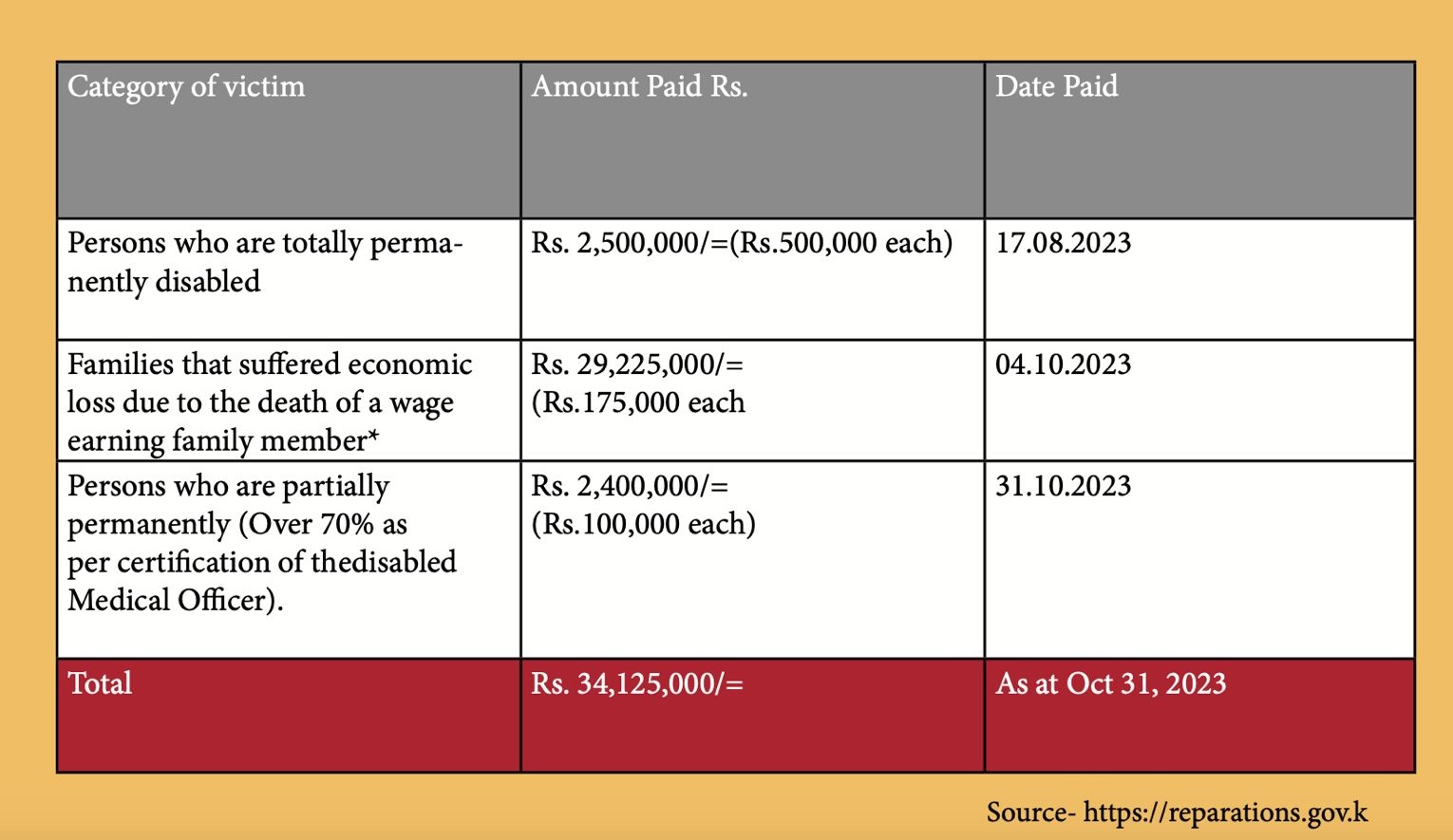

What followed was a flurry of arrests, inquiries, and public commissions. Twelve Fundamental Rights cases filed in the Supreme Court resulted in a landmark ruling: the state and senior officials, including Sirisena and the then-Inspector General of Police, had failed to prevent the attacks. Compensation was ordered, but accountability remained partial.

To date, the main criminal case against 25 accused remains in the early stages of trial. Two senior state officials — former Defence Secretary Hemasiri Fernando and IGP Pujith Jayasundara — were initially acquitted.

In November 2024, the Supreme Court overturned this acquittal, ordering that their defence be heard. Yet the legal gears move slowly.

Meanwhile, other connected cases — such as those against lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah and poet Ahnaf Jazeem — raise concerns over wrongful prosecution and state overreach under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. These cases serve as reminders of a justice system that appears both selective and misdirected.

Beyond the courts, the real cost of the attacks is borne in silence. Survivors continue to struggle. The Malaiyaha Tamil community in particular, already marginalized, lost breadwinners and bore the brunt of economic fallout with little recognition, according to a report by the Centre for Society and Religion (CSR).

The CSR warns that without accurately confirming the number of victims, some families risk being unfairly excluded from reparation efforts. It highlights that discrepancies in official data have led to inconsistencies in fund allocation, and urges the government to undertake a thorough verification process to ensure no victim is left out of compensation or support. The report stresses that justice must include recognition — and that begins with acknowledging every life lost.

The Pillayan twist

In 2023, a Channel 4 documentary reignited public scrutiny over an alleged conspiracy, linking Sri Lankan military intelligence and the bombers. The documentary didn’t reveal what Sri Lankans didn’t already suspect. But it said it aloud. And that mattered.

Much of the documentary echoed existing allegations. But it also introduced claims implicating then-State Intelligence chief Suresh Sallay and suggesting a broader conspiracy to engineer a security crisis that would pave the way for Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s 2019 presidential run.

It introduced to public discourse the alleged role of former State Minister, Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan, better known as ‘Pillayan’.

According to the documentary, a former aide of Pillayan claimed to establish the links between Pillayan, Suresh Sallay and the NTJ terrorists.

Though swiftly denied by the then government, the allegations persisted. Two commissions of inquiry, appointed afterwards, compiled reports that are yet to be made public — fuelling renewed calls from civil society and the Catholic Church for transparency and an international probe.

With the election of the NPP government, interest in the investigation resurfaced and investigations were reopened in October 2024.

However, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake stated over the weekend that his government is in no hurry to reveal anything prematurely, despite mounting public pressure. Members of his administration have long hinted at being privy to information that could substantiate claims of a conspiracy to bring the Rajapaksas to power.

Now, he must walk the talk. Immediately after his electoral victory, Dissanayake visited the Katuwapitiya St. Sebastian’s Church, where he was confronted by angry and grieving victims weary of unanswered questions and delayed justice.

During this visit, the President, having heard their grievances, stressed the importance of conducting the investigation without bias or preconceived notions. Yet, the recent arrest of Pillayan has cast fresh doubts on that commitment.

“The next steps of the investigation must be handled with great care. Therefore, you may not be able to know about certain things just yet,” Dissanayake said addressing a campaign rally in Badulla.

He also said that the final report and accompanying documents of the Presidential Investigation Commission on the Easter Sunday attacks were handed over to the CID, assuring that these were full reports and not redacted or documents with pages or sections missing.

The recent arrest of Pillayan in early April added a fresh layer of intrigue with Public Security Minister Ananda Wijepala informing Parliament that evidence had emerged linking Pillayan to the 2019 attacks.

Former MP Udaya Gammanpila who has come forward as counsel for Pillayan strongly disputed this. He said that Pillayan was detained under the PTA in connection with a 2006 abduction case in the Eastern Province — not the Easter attacks. Pillayan had been in remand custody from 2015 to 2020, Gammanpila argued, making involvement in the 2019 bombings implausible.

This comment also contests the picture painted by the Channel 4 documentary, which alleged that it was during Pillayan’s imprisonment that he was acquainted with the NTJ terrorists.

Speaking as Pillayan’s legal representative, Gammanpila also accused the government of misleading the public and violating due process. He claimed CID officials initially denied Pillayan access to legal counsel and that his eventual meeting with Pillayan was conducted under surveillance, violating attorney-client confidentiality. “He broke down,” Gammanpila said, recalling Pillayan’s question: “How many more years must I suffer for helping to end the war?”

Public statements from various quarters grow louder, but the cloud of uncertainty around the Easter attacks has also been growing.

A call unanswered

For the Catholic Church, the call for justice has become a spiritual campaign. Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith has since become a voice of moral outrage, demanding international inquiry, naming names, and refusing to accept silence as an answer, repeatedly.

For others — human rights groups, NGOs, and victims’ collectives — the goal is simpler: the truth. Not just arrests and prosecutions, but a full and honest reckoning of what happened, why it happened, and who allowed it to happen.

Despite court rulings, compensation schemes, and reparation funds, Sri Lanka remains haunted by that April morning. Haunted not just by the deaths, but by the gaps in its democratic memory.

What should have been only the pursuit of truth and justice has instead devolved into a political volleyball match — where blame is deflected, reports are buried, and the pain of survivors is sidelined for power plays.

Six years later, a reckoning awaits. The Easter Sunday attacks were not just a failure of intelligence. They were a failure of leadership, of moral responsibility, of justice. Until justice is served — fully, transparently, and fearlessly — Sri Lanka will carry the weight of this tragedy as a wound that refuses to heal. (Newswire)